It's summer and there is some time to blog about things. This blog post is the first in a series of three posts where we illustrate Crail's raw storage performance on our 100Gbps cluster. In part I we cover Crail's DRAM storage tier, part II will be about Crail's NVMe flash storage tier, and part III will be about Crail's metadata performance.

I recently read the Octopus file system Usenix'17 paper, where the authors show Crail performance numbers that do not match the performance we measure on our clusters. Like many other distributed systems, Crail also requires a careful system configuration and wrong or mismatching configuration settings can easily lead to poor performance. Therefore, in this blog we try to point out the key parameter settings that are necessary to obtain proper performance numbers with Crail.

Hardware Configuration

The specific cluster configuration used for the experiments in this blog:

- Cluster

- 8 node OpenPower cluster (for Crail)

- 2 node X86 cluster (for RAMCloud)

- OpenPower Node configuration

- CPU: 2x OpenPOWER Power8 10-core @2.9Ghz

- DRAM: 512GB DDR4

- Network: 1x100Gbit/s Ethernet Mellanox ConnectX-4 EN (Ethernet/RoCE)

- RDMA send/recv latency, ib_send_lat (RTT): 3.1us

- RDMA read latency, ib_read_lat (RTT): 2.3us

- Software

- RedHat 7.2 with Linux kernel version 4.10.13

- Crail 1.0, internal version 2842

- Alluxio 1.4

- RAMCloud commit f53202398b4720f20b0cdc42732edf48b928b8d7

Anatomy of a Crail Data Operation

Data operations in Crail -- such as the reading or writing of files -- are internally composed of metadata operations and actual data transfers. Let's look at a simple Crail application that opens a file and reads the file sequentially:

CrailConfiguration conf = new CrailConfiguration();

CrailFS fs = CrailFS.newInstance(conf);

CrailFile file = fs.lookup(filename).get().asFile();

CrailInputStream stream = file.getDirectInputStream();

while(stream.available() > 0){

Future<Buffer> future = stream.read(buf);

//Do something useful

...

//Await completion of operation

future.get();

}

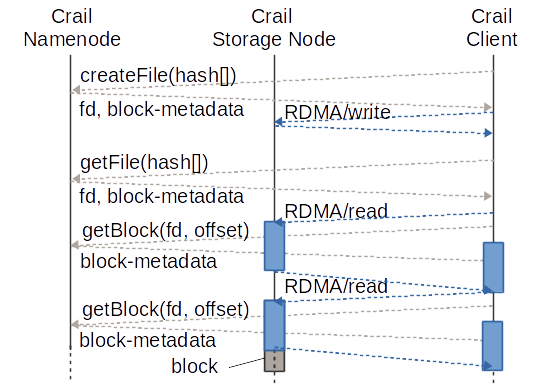

One challenge with file read/write operations is to avoid blocking in case block metadata information is missing. Crail caches block metadata at the client, but caching is ineffective for both random reads and write-once read-once data. To avoid blocking for sequential read/write operations, Crail interleaves metadata operations and actual data transfers. Each read operation always triggers the lookup of block metadata for the next block immediately after issuing the RDMA read operation for the current block. The asynchronous and non-blocking nature of RDMA allows both operations to be executed in the process context of the application, without context switching or any additional background threads. The figure illustrates the case of one outstanding operation a time. The asynchronous Crail storage API, however, permits any number of outstanding operations.

As a side note, it's also worth mentioning that Crail does not actually use RPCs for the data transfers but uses RDMA one-sided read/write operations instead. Moreover, Crail is designed from ground up for byte-addressable storage and memory. For instance, files in Crail are essentially a sequence of virtual memory windows on different hosts which allows for a very effective handling of small data operations. As shown in the figure, during the last operation, with only a few bytes left to be read, the byte-granular nature of Crail's block access protocol makes sure that only the relevant bytes are transmitted over the network, as opposed to transmitting the entire block.

The basic read/write logic shown in the figure above is common to all storage tiers in Crail, including the NVMe flash tier. In the remainder of this post, we specificially look at the performance of Crail's DRAM storage tier though.

Sequential Read/Write Throughput

Let's start by looking at sequential read/write performance. These benchmarks can be run easily from the command line. Below is an example for a sequential write experiment issuing 100M write operations of size 1K to produce a file of roughly 100GB size. The -w switch indicates that we are using 32 warmup operations.

./bin/crail iobench -t write -s 1024 -k 100000000 -w 32 -f /tmp.dat

Crail offers direct I/O streams as well as buffered streams. For sequential operations it is important to use the buffered streams. Even though the buffered streams impose one extra copy (from the Crail stream to the application buffer) they are typically more effective for sequential access as they make sure that at least one network operation is in-flight at any time. The buffer size in a Crail buffered stream and the number of oustanding operations can be controlled by setting the buffersize and the slicesize properties in crail-site.conf. For our experiments we used a 1MB buffer per stream sliced up into two slices of 512K each which eventually leads to two operations in flight.

crail.buffersize 1048576

crail.slicesize 524288

The figure below illustrates the sequential write (top) and read (bottom) performance of Crail (DRAM tier) for different application buffer sizes (not to be mixed up with crail.buffersize used within streams) and shows a comparison to other systems. As of now, we only show a comparison with Alluxio, an in-memory file system for caching data in Spark or Hadoop applications. We are, however, working on including results for other storage systems such as Apache Ignite and GlusterFS and we plan to update the blog post accordingly soon. If there is a particular storage system that is not included but you would like to see included as a comparison, please write us. And important: if you find that the results we show for a particular storage system do not match your experience, please write to us too, we are happy to revisit the configuration.

One first observation from the figure is that there is almost no difference in performance for write and read operations. Second, at a buffer size of around 1K Crail reaches a bandwidth close to 95Gbit/s (for read), which is approaching the network hardware limit of 100Gbps. And third, Crail performs significantly faster than other in-memory storage systems, in this case Alluxio. This because Crail is built on of user-level networking and thereby avoids the overheads of both the Linux network stack (memory copies, context switches, etc.) and the Java runtime.

Note that both figures show single-client performance numbers. With Crail being a user-level storage system executing I/O operations directly within the application context this means the entire benchmark is truly runninig on one single core. Often, systems that perform poorly in single-client experiments are being defended saying that nobody cares about the single-client performance. Especially throughput problems can easily be fixed by adding more cores. This is, however, not at all cloudy to say the least. At the level hardware is multiplexed and priced in today's cloud computing data centers every core counts. The figure below shows a simple Spark group-by experiment on the same 8-node cluster. As can be seen, with Crail the benchmark executes faster using a single core per machine than with default Spark using 8 cores per machine, which is a direct consequence from Crail's superb single-core I/O performance.

Random Read Latency

Typically, distributed storage systems are either built for sequential access to large data sets (e.g., HDFS) or they are optimized for random access to small data sets (e.g., key/value stores). We have already shown that Crail performs well for large sequentially accessed data sets, let's now look at the latencies of small random read operations. For this, we mimic the behavior of a key/value store by storing key/value pairs in Crail files with the key being the filename. We then measure the time it takes to open the file and read its content. Again, the benchmark can easily be executed from the command line. The following example issues 1M get() operations on a small file filled with a 4 byte value.

./bin/crail iobench -t getkey -s 4 -k 1000000 -f /tmp.dat -w 32

The figure below illustrates the latencies of get() operations for different key/value sizes and compares them to the latencies we obtained with RAMCloud for the same type of operations (measured using RAMClouds C and Java APIs). RAMCloud is a low-latency key/value store implemented using RDMA. RAMCloud actually provides durable storage by asynchronously replicating data onto backup devices. However, at any point in time all the data is held in DRAM and read requests will be served from DRAM directly. Up to our knowledge, RAMCloud is the fastest key/value store that is (a) available open source and (b) can be deployed in practice as a storage platform for applications. Other similar RDMA-based storage systems we looked at, like FaRM or HERD, are either not open source or they do not provide a clean separation between storage system, API and clients.

As can be seen from the figure, Crail's latencies for reading small files range from 10us to 20us for files smaller than 256K. The first observation is that these latency numbers are very close to the RAMCloud get() latencies obtained using the RAMCloud C API. Mainly, the latency difference between the two systems comes from the extra network roundtrip that is required in Crail to open the file, an operation which involves the Crail namenode. Once the file size reaches 64K, the cost for the extra roundtrip is amortized and the Crail latencies start to match the RAMCloud latencies. The second observation from the figure is that Crail offers lower latencies than the RAMCloud Java API for key/value sizes of 16K and bigger. This is because Crail, which is implemented in Java itself, integrates natively with the Java memory system. For instance, Crail's raw stream APIs permits clients to pass Java off-heap ByteBuffers which can be accessed by the network interface directly, avoiding data copies along the way. That being said we also understand that the Java API is not RAMCloud's primary API and could probably be optimized further.

All in all the main take away here is that -- despite Crail offering a fully hierchical storage namespace and high-performance operations on large data sets -- the latencies for looking up and reading small data sets are in the same ballpark as the get() latencies of some of the fastest key/value stores out there.

The latency advantages of Crail are beneficial also at the application level. The figure below illustrates this in a Spark broadcast experiment. Broadcast objects in Spark are typically small read-only variables that are shared across the cluster. The Crail broadcast module for Spark uses Crail as a storage backend to make broadcast variables accessible by the different tasks. As can be seen, using Crail broadcast objects can be accessed in just a few microseconds, while the same operation in default Spark takes milliseconds.

To summarize, in this blog post we have shown that Crail's DRAM storage tier provides both throughput and latency close to the hardware limits. These performance benefits enable high-level data processing operations like shuffle or broadcast to be implemented faster and/or more efficient.